Your Organization's Social Media Strategy Sucks - Part 1

The business as usual approach to social media by outdoor and environmental groups are ceding ground to right wing groups on important issues with young voters

A note from Len: This is the first post of a two-part series; I decided to separate this conversation into a few posts as the length and complexity of this issue have required it. Thanks to Teal Lehto for helping me write and providing a huge part of the brain power for the analysis of this piece.

As someone who is online way too much, I’ve been able to take stock of norms and trends that permeate the online spaces where I work. What I’m seeing concerns me. I deeply care about environmental and social issues; however, I often find myself scrolling past or rolling my eyes at how messages are shared through social media channels by organizations that ostensibly are the ones who are doing the most work to affect this change in these areas. Since it’s an election year, the space will be flooded with messaging intended to shape a broader political narrative, inflame, dissuade, drive action, coerce inaction, or other motivations that come with a politically contentious environment. It’s been a while since I’ve thrown a bomb into the professional realms in which I work; however, it’s time: most of the social content put out by nonprofits and advocacy sucks and, in many respects, is operating with assumptions that made sense a decade ago. If a new playbook that meets the time and information economy we’re living in isn't adopted, we (those on the left) will continue to lose ground on important issues to those winning the attention economy who often work against the issues we care about.

Social media exists in a segment of the real economy and a fictitious, albeit very real, one called the “Attention Economy.” The idea of attention economics was first theorized by psychologist and economist Herbert A. Simon was born in 1971 - nearly 12 years before what we consider the internet today- in 1983. This concept has become increasingly salient in recent decades with the rise of internet content (supply) and our attention becoming scarce in this context. Davenport and Beck (2001) defined the “economics of attention” as an approach to managing information that treats human attention as a scarce commodity and applies economic theory to solve various information management problems. A key piece of Simon’s theory that relates to where we find ourselves today is that we are incorrectly approaching social media through a lens of information scarcity (e.g., “our point of view isn’t getting out into the world, we need to double down”) versus one of attention scarcity (e.g., “the attention of people we are trying to reach is already overloaded how do we break through the noise”). Think about how many different ways your attention is split daily and how often you scroll by messages on important topics like climate change and voting each day.

What is fed to you in these social feeds largely depends upon the unique algorithmic gardens we all create online. The invisible hand of algorithms (more accurately, algorithmic recommendations) drives the broader narrative in online spaces. These recommendations are largely individualized algorithms (and probabilistic categories) depending on direct and indirect measures of “affinity” based on user behavior on these platforms. What these algorithms prioritize largely depends on how much they hook people’s attention and what keeps people on platforms. At the risk of oversimplifying the role of algorithms, even amid mindless scrolling, we are planting in our algorithmic garden by engaging with content we like and weeding content we don't. Broader changes to these probabilistic models or engagement with content and users outside these confines can also change our garden. The role and impact of these algorithms aren’t just limited to the content we engage online. Taylor Lorenz, a reporter for the Washington Post on internet culture, has noted that algorithms can shape how we speak and the cultural norms that take hold in society. In these algorithms and scarcity of attention is the need to craft messaging and platforms that engage and continually hold people’s attention.

Why does this matter? An increasing and sizeable portion of the U.S. population gets their news primarily from social media, which is increasingly subject to algorithmic curation. Younger people, largely under 30, primarily use social media as their main source of information, and it has increased significantly on platforms like Instagram and TikTok. For factual and vetted information to be seen by many people, it must be presented in a compelling format and effectively work within the algorithmic ecosystem. Good information alone will not rise to the top. Far more people can see misinformation packaged in compelling content. At first glance, this challenge may seem like a Rube-Goldberg machine of complexity; however, the solution to this is straightforward, and right-wing actors are effectively utilizing it.

Enter the BlueRibbon Coalition & PowellHeadz: Effectively Using Social Media To Spread Brain Dead Rightwing Talking Points On The Environment

According to Monitoring Influence,

BlueRibbon Coalition is an association of off-highway vehicles and related industry groups that promote motorized vehicle access to public lands while using overblown and misleading rhetoric to oppose conservation efforts.

Over the past few years, I’ve seen the growth of the BlueRibbon Coalition’s (BRC) social media channels and their ability to seed narratives within the broader public. This growth, in part, was aided by a partnership they developed with a part-time landscaper / part-time musician / part-time influencer named Zach Smoot, who runs PowellHeadz - effectively a Lake Powell Vibe page. Initially, I dismissed them as a fringe right-wing group spreading misinformation; however, this view shifted dramatically when I heard acquaintances in the outdoor space parroting BRC talking points about trail closures around Moab. Looking further into their online presence, they can spin and craft deceptive narratives and misinformation to suit their political aims through fairly simple social media strategies. Monitoring Influence highlights a few such examples:

BRC Claims Updated Management Plans Are “Wilderness Laundering” By Proposing New Areas To Designate As Wilderness. “You will find as the BLM and Forest Service update management plans, they propose areas that could potentially become wilderness. We call this wilderness laundering. There are currently management plan and travel management plan proposals in Utah, Colorado, Nevada, South Dakota, Wyoming, Arizona, New Mexico, Idaho, Oregon and Montana with more to come. BRC is involved with these plans every step of the way. We need you to comment, to discourage the creation of these areas.” [Fight for Every Inch, Sharetrails.org, accessed 05/23/2022]

The coalition, which also calls itself “ShareTrails,” opposes the Biden Administration’s America the Beautiful Conservation initiative that aims to conserve 30% of lands and waters by 2030, erroneously calling it a “clear effort to lock people out of their land.”

Though membership dues make up a significant amount of BRC’s income, the group gets most of its money from grants from the OHV industry. In the past, BRC received major donations from corporations including Exxon

Leadership in the organizations I’m trying to speak to will likely say so what if groups like this get more engagement online? My answer is simple: they set the tone for online conversation on important issues. Their misinformation is reaching more people than environmental groups, and consequently, their call to action is leading to a wonderful parroting of their talking points in public comments in policy-making processes. Notably, BRC & PH have spread misinformation that Lake Powell has reached record low levels recently because the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) has let too much water out (no mention of the 20-year drought or Climate Change in the basin). Last October I got sent a few gems of public comments from the BOR’s SEIS public comment period that reflected these talking points. Let’s just say they are entertaining in their stupidity.

California is draining the water into the Ocean (isn’t that how rivers work?)

Keep water in Lake Powell!!!!!! California is draining water into the ocean they dont need it!!!!

You guys are letting TOO MUCH water out of Powell! The Antelope Point Marina needs to be usable!

This one is nice and unhinged:

STOP RELEASING WATER FROM LAKE POWELL. I GREW UP IN THIS LAKE. HAD A HOUSE BOAT FOR 10 YEARS ON THIS LAKE IN THE 90s. I CAN NO LONGER TAKE MY KIDS TO SEE ALL THE BEAUTIFUL CANYONS I SAW BECAUSE THERE IS NO WATER LEFT. YOU PEOPLE HAVE RUINED THIS LAKE. IT IS DISGUSTING WHAT YOU ARE DOING. WHY ON EARTH WOULD YOU WANT TO EMPTY THIS LAKE. GREEDY MUCH JUST STOP. STOP WASTING ALL OF POWELLS WATER. STOP RUINING FAMILY TRIPS. STOP RUINING PARENTS AND GRANDPARENTS THE RIGHT TO LET THEIR FAMILIES EXPERIENCE WHAT WE DID MANY YEARS AGO. KEEP POWELL FULL. STOP WASTING AND RELEASING WATER NOW

This one made my brain hurt trying to read it:

I would love to see the lake stay fuller in the winter and think that less water should be let out, to conserve or water here, on lake powell.

The irony of “it’s bigger than you” when talking about water use on the Colorado River:

Just keep lake Powell alive! Tons of people go every year and enjoy it. It is a staple trip for tons of families. It helps provide money for people that use the water. You can'y t just drain the lake for your selfish reasons and money. It's bigger than you. Keep Powell alive.

The secret sauce of the right-wing anti-environmental media: accessibility and avoiding elitism.

What makes these groups’ social media effectively drive people to parrot their dumb messages? They have a folksy executive director, Ben Burr, and Reservoir Influencer, Zach Smoot, who easily translates complex policy issues into simple black-and-white narratives of good-vs-evil. It’s a simple and effective strategy since most Americans read at a seventh- or eighth-grade level, and playing into partisan divides is an easy way to stoke the algorithmic fire.

Below is a simple comparison of the differences in the approaches. One caption is from a large environmental organization (we won’t name names), and one is from the Blue Ribbon Coalition (they had few captions and primarily relied on video). The comparison uses a test of reading level using the Flesch-Kincaid readability tests.

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of the provided text is approximately 16.41. This indicates that the text is appropriate for college graduate readers. This example text came from a large left-leaning environmental organization.

Last week, @potus expanded two national monuments in California: the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument in Southern California and the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument in Northern California. This effort has been decades in the making, and the expansions protect nearly 120,000 acres of public lands combined. This action will help ensure Californians’ access to nature, protect important cultural landscapes and preserve critical wildlife habitat.

This text's Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level is approximately 5.24, which indicates that it is appropriate for readers at about a 5th-grade reading level. It came from the Blue Ribbon Coalition.

5 ways BRC will fight to #SAVEMOAB and how you can help too:

📣Action 1: We Will Challenge This Plan In Court

📣Action 2: We Need to Pressure Congress to Stop This Plan

📣Action 3: We Need to Control the Media Narrative Around this Fight and Others

📣Action 4: We Need to Encourage Industry, Club, and Organization Support

📣Action 5: Order a Copy of the Lost Trails Guidebook and Explore the Trails

To read the detailed plan, visit link in bio

To demonstrate why this difference in reading level matters, I’ll ask you a rhetorical question: How many people have completed elementary school versus graduate school in the United States? About near universal completion vs about 13.7% of the population. Messaging that talks over people’s heads is less likely to land with them. It’s not that complicated. If you aren’t reaching people where they’re at, you’ll have difficulty selling them your point of view or argument. The social scientist in me realizes that making one comparison to draw a conclusion is not a good practice; however, I'd be willing to wager that, on average, left-leaning environmental organizations are writing at a much higher reading level than those folks at BlueRibbon.

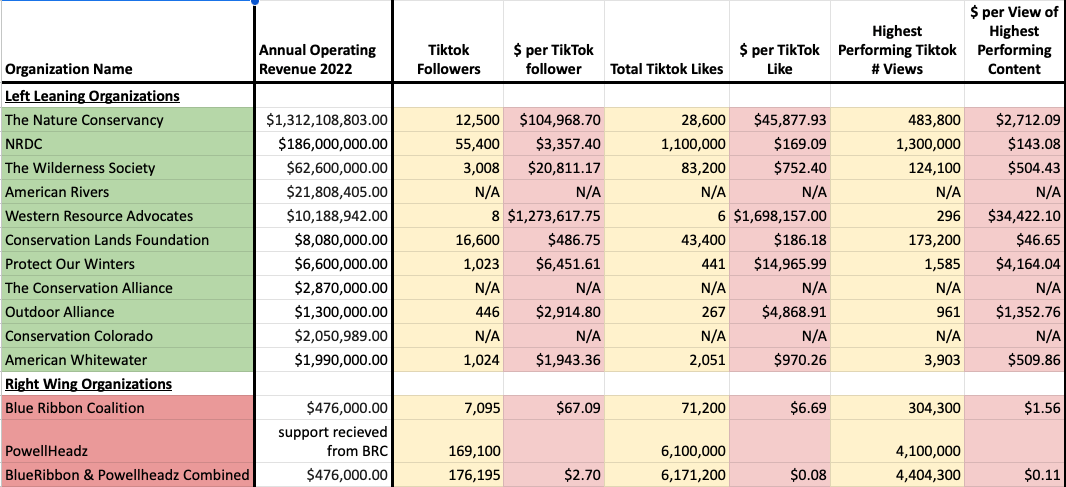

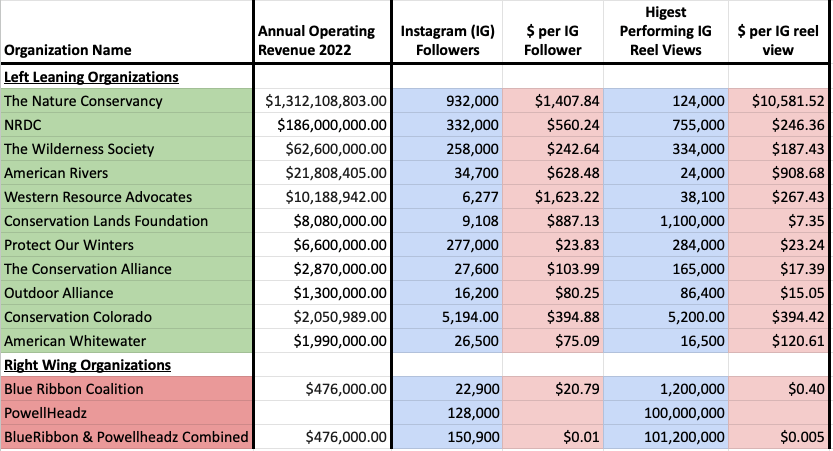

I decided to do a quick back-of-the-envelope assessment of how BlueRibbon’s strategy compares with larger left-leaning environmental organizations. My hypothesis is simple: larger organizations with much larger budgets should perform at a much higher level on social media in reach and engagement than smaller organizations. Secondly, these organizations should have economies of scale working in their favor, given their budgets. Using these hypotheses, I surveyed a handful of environmental organizations’ total number of followers, total likes, and total views of their highest-performing posts on TikTok and Instagram. I created a set of efficiency metrics using these numbers and the organization’s 2022 annual operating revenue sourced from ProPublica. These metrics are a quick measure of social media efficiency: $ per follower, $ per like, and $ per view of highest-performing content. You can view the data here.

Looking at this data, it becomes exceedingly clear how much a group like BlueRibbon can outperform its peers online despite its small annual operating budget simply by creating better content. Across the board the efficiency metrics are orders of magnitudes smaller than their peers’. This is important because a group like BlueRibbon, while unable to spend large amounts of money on lobbying or other high-cost activities, can have a significant and disruptive effect on specific campaigns led by environmental groups by riling up local populations or demographics. This becomes increasingly more acute when you combine messaging from environmental groups that talk over the heads of locals and a BlueRibbon-type organization that creates more accessible information. This reality is already playing out before us.

Part 2 is in the works

As a short preview of Part 2, I decided to look behind the curtain of the social media of several environmental and outdoor-focused organizations to better understand what’s driving their strategy and decision-making. I talked with several social media managers who are in the trenches of the online meme wars and got their takes on what’s driving such poor messaging strategies from their organizations. Many organizations are white-knuckling social media, scared about imagined repercussions of “doing the wrong thing,” and strategy is driven by those at the top who rarely use the platforms. What I found surprising was how uniform their sentiments about the effectiveness of their messaging were and how similar the identification of root causes of the issue was across multiple organizations.

Expect to see this next post in the coming week.

As the comms director for a national environmental nonprofit, this should be mandatory reading for comms (and leadership) staff. We (the collective "we" of nonprofits) waste hours and hours of staff time "managing" social media, which ultimately results in boring, milk toast content that no one sees or engages with just so we can say we "did" social media. I have a hunch that we are ultimately afraid to actually grab people's attention because then we might receive criticism and lord, left leaning nonprofits are TERRIFIED of receiving criticism. But you know who aren't afraid of criticism? Right wing advocacy groups. So they win on content, messaging, and branding. Every. Single. Time.

Really great stuff, Len. Looking forward to part 2.