What Lasts

A drive through Baja to see 9,000-year-old cave paintings—and reckon with what we leave behind

The first sound was water.

Not rain. Not waves. Just a slow, steady drip from somewhere above the windshield, tapping the front of the cabin like a metronome that had decided to become personal. I lay there trying to place it, still half inside sleep, still expecting the rules of Tucson to apply. Then the van gave me the answer. Condensation. The windows had turned into cold stone, and the air had turned into breath.

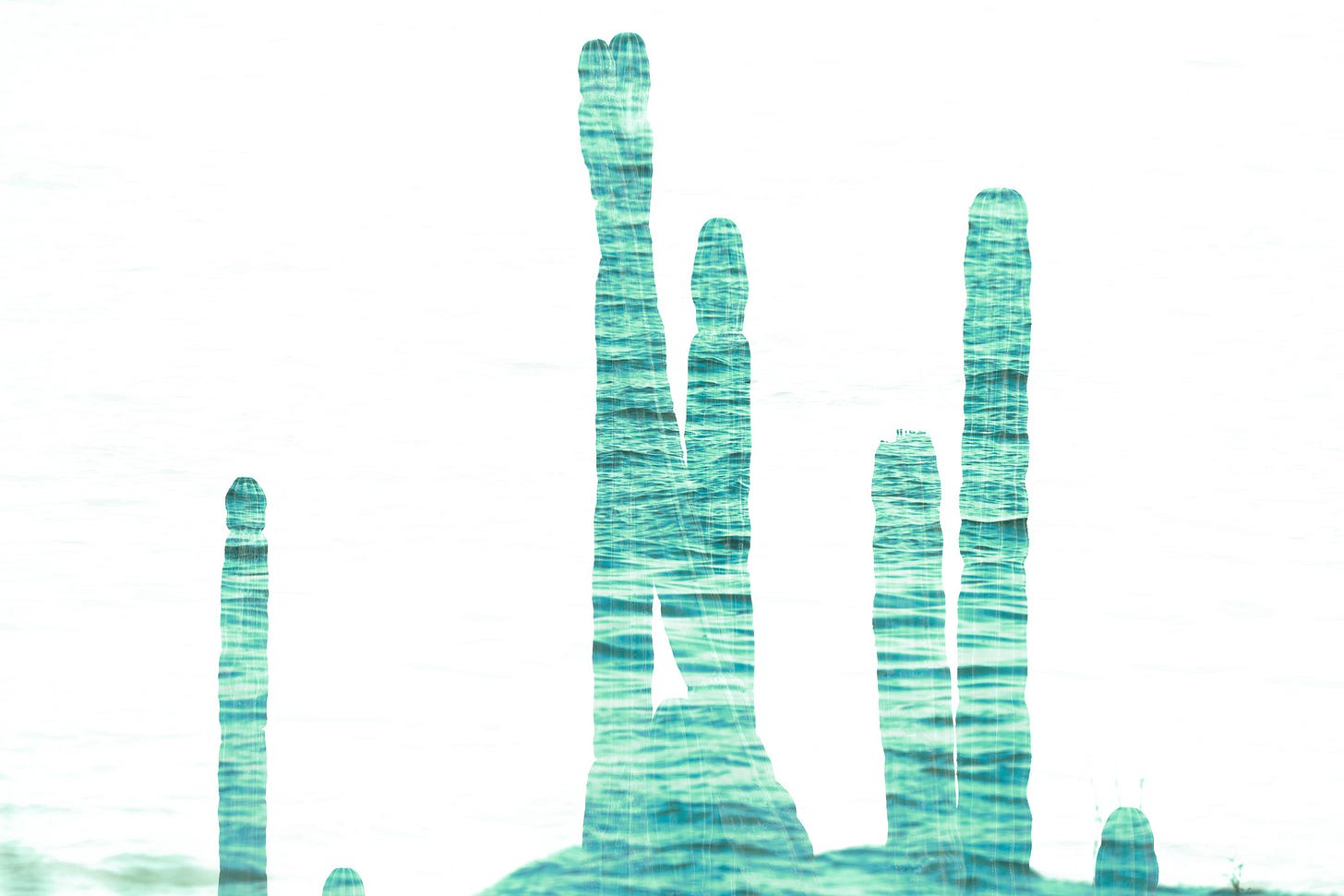

When I sat up, the world outside was enshrouded by mist. Fog had settled into the valley with the patience of something that didn’t need to move fast to win. The cacti were there in silhouette, but the edges had softened. Distance stopped behaving like a measurement and started behaving like a mood. The few-hundred-foot mesa above me looked like a towering mountain range.

The fog made the desert illegible, which was the point.

I had arrived late the night before, after hours of washboard and a road that refused to offer easy landmarks. Out there, the desert is not the austere minimalism people project onto it. Up close, it’s crowded. Creosote, organ pipes, hecho-like shadows, spines, resin, the hard little architecture of plants that have learned to turn scarcity into a career.

I stepped outside, and the cold surprised me. Not mountain cold, but the kind that only happens when a desert borrows the ocean’s breath. Everything smelled sharpened. Creosote is usually a memory of rain. Here, it was a memory of the sea.

The fog made the cacti look older than they are—gave them that specific presence where you stop thinking of them as plants and start thinking of them as witnesses. When the wind moved through them, it didn’t make a rustling sound; it made something quieter, more like cloth shifting.

The light came slowly. First, a deep marine blue that had no business in a desert, then a paleening at the horizon, then the fog itself brightened as if someone had turned a dimmer knob inside it.

There are Indigenous stories where the earliest human worlds were not crisp. In Diné bahane’, the First World is a place of black mist, a darkness inhabited by beings who existed but hadn’t yet decided what they were—Insect People, spirit forms, potential without fixed shape. Emergence happens slowly, world by world, each one more defined than the last. The journey upward isn’t just movement through space. It’s a process of becoming, reality accumulating layer by layer, nothing arriving whole.

I had left Tucson with everything too fixed. The categories were sharp, the obligations familiar, the loop so worn I couldn’t feel its edges anymore. The fog undid that. Standing in the mist, the world felt new again—not blank, but *prior*, like the moment before a shape commits to being a shape. Some mornings you wake up inside the in-between. That morning, I needed it.

The fog made the world temporary in a way that felt clarifying. It made the desert stop performing for me. It wasn’t offering a panorama. It wasn’t giving me the easy reward of scale. It was saying: if you want to see, you’re going to have to walk into it.

So I did.

A few days earlier

By the time I reached the border, I had already decided what I wanted from it.

Not a rite of passage, not a flex. I was seven years into building a business, just wrapping one of the biggest projects we’d been part of—a film about the American Southwest that had taken everything I had to give it. The work was done. The question it left behind wasn’t. *What’s next* is the polite version. The real version is older and less comfortable: *what is this all for?* It comes up again and again, usually when I’ve been moving too fast to hear it. I hadn’t stopped to reflect until then. I’d just kept producing, kept delivering, kept letting the momentum answer the question for me.

A border interrupts that. It doesn’t ask politely.

At Lukeville you don’t have some neat outbound ceremony on the U.S. side. You slide past hulking X-ray machines built to swallow semis, a spaceport dropped into a desolate Star Wars desert outpost, and roll over the speed bumps toward the gates in the border wall. The gates are usually open in a way that feels semi-permanent, but not permanent enough to let you forget what they are. There’s no handshake with authority, just the quiet knowledge that the state has built a mouth here and you are choosing to enter it.

Mexico meets you in layers. First, the military. They pulled me out of the queue right after I passed the border wall. It wasn’t a deep inspection—more a gesture, a reminder that you are entering a country with its own anxieties and its own muscle memory about weapons. You answer the questions, you stay calm, you let your posture say: I’m not here to make your day harder.

Then the street economy begins. Guys hawking windshield cleaning, small transactions popping up in the exhaust. On the U.S. side, everyone is trapped in their vehicles. Here, the vehicles are only part of the scene.

I also hate crossing. Not in an abstract way. In a body way. The stomach tightening even when nothing is happening, the awareness of skin and accent and name inside your own skull. The border does not feel neutral, and it feels less neutral lately, even when it goes fine.

I drove southeast toward Puerto Peñasco through that strange hybrid zone where Mexico is softened for American consumption—beach culture built like a compromise. I’m not interested in shaming anyone’s vacations. I’m just not built for that particular kind of safety. It feels like being in a theme park where the rides are real people.

I wanted the hard edge where the desert meets the sea without a buffer zone. Baja has that feeling. The desert doesn’t gradually become coastal. It just ends, and then there’s water. A cut.

The road language changes with the border. A two-lane highway with shoulders behaves like a three-lane road because the middle becomes a shared passing lane, and the shoulders become overflow where slower vehicles slide right to make room. Big trucks will flick on a left blinker to tell you it’s safe to pass. You move out, commit, clear the bumper, blink your hazards as thanks. It’s a small vocabulary of mutual dependence, and it only works because everyone is paying attention.

I’m not going to do the travel-writer thing where Mexico gets flattened into either danger porn or a safe “hidden gem.” The risks out here are real. I don’t drive at night. I have a plan for where I’m sleeping and a plan for when the plan breaks. I’ve met men with guns in remote parts of this country who weren’t police or military, and the kindest thing they did was signal for me to turn around.

Somewhere after the first military checkpoint, rhythm settled in. Not because the risks disappear. But the mental noise I was trying to outrun thins. The emails aren’t gone. The world isn’t fixed. The border doesn’t redeem you.

It does something simpler. It makes the day stop feeling like a copy of itself.

Campo La Salina

This is where the sky gets held.

At Campo La Salina, the land is flat enough to behave like a mirror when it wants to. A recent rain had left a shallow pool across the playa, and the water sat there without ambition, reflecting clouds so cleanly it looked less like weather and more like an edit. The salt crust was already returning along the edges, brightening into a thin rind as the center slowly evaporated.

The place announces itself as a working landscape before it announces itself as a beautiful one. There’s an ejido presence, a few structures, the straightforward signage of somewhere that makes its living by staying put. It’s not a resort, not a nature preserve performance.

I’m careful with the word pilgrimage because it can turn saccharine fast. But the pull of this coast has always been older than recreation. There are ethnohistorical accounts of O’odham ritual trips to the coast for salt, and the archaeology sits there like corroboration—a long record of people who kept coming back for thousands of years.

And then there’s the engine under the beauty. The northern Gulf is a place where the physics are always turned up. The tidal range is enormous, generating strong currents and moving sediment like the shoreline is never finished making itself. Prevailing winds pick up sand and move it inland, building dune fields that run for tens of kilometers into the Gran Desierto. If you’re not used to this kind of coast, it feels like the ocean is collaborating with the desert. The sea lays out a flat of wet sand. The wind steals it.

Historically the upper Gulf was tied to the Colorado River’s seasonal floods—pulses of sediment, nutrients, and freshwater that supported phytoplankton blooms and a rich food chain. Even now, with the river functionally removed from its delta for most years, you can still feel the ghost of it in the geometry.

The science has a blunt phrase for what the river’s absence has done. With freshwater eliminated, the system becomes an inverse estuary—saltier toward the head and less salty toward the open gulf. The coast turns into a concentrator. Heat and evaporation do what they do in Sonora, and the salt flats are what’s left behind.

I walked out onto the playa and the salt crunched underfoot, a dry, mineral sound that felt like the landscape announcing itself. Closer to the water, the crunch shifted—seashells now, dense and pale, layered over dark sediment that the tide had exposed. That darker layer is the delta’s ghost, still shaping what the coast can be even with the river gone. By sunset the wind came up hard, the kind that pushes at your chest and makes you turn your back to it. Then, an hour later, calm. The gulf holding its breath.

The coast is full of shells because it has been full of life. It is also full of shells because it has been full of people. Those are not the same statement, but they are related.

Juan and the comedy of preparation

Juan is the caretaker here, which is a job title that contains more than it admits.

At Campo La Salina, “caretaker” doesn’t mean ranger or curator. It means the person who sits close enough to a place to know its moods, who keeps the practical machinery of access running, who remembers what happens when the sand looks firm and isn’t.

The first time I met him, he warned me not to get stuck. He said it lightly, without performance: “No te vayas a atorar.”

I got stuck anyway.

There’s a specific kind of humiliation that comes with burying a vehicle in a landscape that is otherwise empty. No audience, no drama, just you and your own miscalculation. The sand isn’t hostile. It just behaves like sand.

Juan came out laughing. Not cruelly. The laugh had the warmth of someone who has seen this enough times to find it funny and still chooses to help. As he dug, he kept saying “Yo te dije,” over and over—a phrase that manages to be affectionate and humiliating in the same breath. It was his way of keeping the story honest. Yes, he would pull me out. No, I didn’t get to pretend it was inevitable.

This time, when I pulled in again, he remembered me.

That mattered more than it should have. Being remembered makes it harder to treat a place like a backdrop. The “remote coast” you came to photograph is also someone’s daily geography, someone’s responsibility, someone’s livelihood.

I told him I was better prepared this time. A shovel that wasn’t decorative. Traction boards. An air compressor I actually trust. He laughed when I said it and seemed genuinely happy to see me again.

The comedy of the “yo te dije” story is that it’s simple. I ignored a warning and paid for it. But the bigger point is that the landscape keeps teaching the same lesson until you learn it, and the people who live alongside it become translators. Juan is one of those translators. He doesn’t preach. He just tells you, calmly, what the place is going to do to you if you don’t respect it.

Footprints, dunes, and the question of persistence

I drove out onto the flats and parked where the geometry took over.

A recent rain had left a shallow pool across the playa. The edges were whitening, the salt recrystallizing in a brittle band where evaporation had started to win. The center stayed darker, reflective enough that the horizon doubled. I walked out until the salt changed under my boots. The first steps were easy, then the surface began to sound different—a faint crunch, a brittle crackle, the crust giving small dry syllables under pressure.

I started thinking about footprints.

How long would my tracks last here. On the dunes behind me, the answer felt obvious. Sand is impatient. It edits constantly. Give it enough wind and the surface resets in minutes. But the salt was different. The flat felt like a ledger.

Each footprint was a shallow depression with crisp edges, the tread pattern visible in a way that felt almost rude. It made me wonder what the minimum conditions are for something to persist. Not forever. Just longer than you expect.

The dunes told one story. The salt told another. The sea told a third.

Toward the waterline, the tide had cut a clean edge and exposed what sits underneath: hard, dark mudrock, compacted and slick. The “beach” here is a thin skin over something older. That darker underlayer is a reminder that this end of the gulf has always been about sediment and rearrangement, the delta’s long afterimage still shaping what the coast can be.

A landscape that makes you wonder about the durability of your own presence is doing its job. It’s reminding you that most of what you do is temporary, and that the things that last often last because the environment chooses to hold them, not because you deserve it.

Mexicali and the giant bird

From Campo La Salina, I cut back inland and crossed the Mexicali Valley, trading salt air for a kind of working haze. Dust, irrigation mist, exhaust, heat shimmer, the soft blur of a place that grows things at industrial scale.

It is hard to remember, driving through it, that this basin used to be something else. The Colorado River once arrived here as a living, branching thing, building land and then rearranging it. Now the geometry belongs to agriculture and industry. Straight lines. Rectangles. Water that moves because someone tells it to.

The first time I saw the bird, I wasn’t even here.

I saw it on Google Earth, the way modern people discover “remote” places now: by hovering over them from a desk, dragging the cursor like a little god. It was a shock because Mexicali doesn’t feel like the kind of place that has secrets big enough to read from space. And yet there it was—a huge figure laid into the desert floor of a caldera.

Cerro Prieto sits in the valley’s fabric like a blunt piece of geology that refused to be smoothed into farmland. The geothermal plant is nearby, the largest of its kind in the world, pulling energy out of heat that never asked permission to exist. Then, not far off, the ground itself becomes the page.

From above, the figure resolves: *El Zopilote Aura*, the turkey vulture, dark stones arranged into thick lines you can read at 20,000 feet.

A local newspaper quoted the artist, Xe Juan Hernández. The bird is a compass. Its head points west, its tail east, one wing north, the other south. It carries twelve feathers for the months. Its navel sits at the chakra of the volcano.

I kept thinking about why he made it. Not the symbolic explanation—the compass, the months, the chakra of the volcano. The other why. The one that doesn’t fit neatly into an artist statement. Sometimes you make something because it’s beautiful. Sometimes because it’s cool. Sometimes because the urge to leave a mark is so old it doesn’t need a reason, just a surface and enough time to commit.

Around the bird, the ground is covered with names. Scratched into the pale earth, spray-painted onto rocks, carved with whatever was handy. Most of them will be gone in a decade. Wind, rain, new names layered over old ones. It’s the same impulse as the bird, just smaller, less patient. *I was here. Remember me.*

I like the audacity of that. Not the national-symbol part. The insistence that a place everyone treats as a pass-through still has a center. That it can be oriented. That it can be read.

It also puts Indigenous time back into a landscape that modernity has tried to bleach into utility. Mexicali is often described as dusty, not worth visiting, as if production is a moral failing. But the valley is also an archive, layered. The industrial present sits on top of older human geographies, which sit on top of older ecologies. The bird doesn’t clean any of that up. It just makes the layering visible.

The cave

By the time the fog settled into the valley, I’d already forgotten what “clear” was supposed to look like. Outside, cirios stood in the mist like antennae, trees designed by an academic committee that only knew what trees were in theory.

There were military checkpoints often enough that you started measuring distance by them. Men in fatigues, loaded assault rifles, the same questions delivered like routine. A blunt reminder that the security situation here isn’t theoretical.

The turnoff to the paintings didn’t announce itself. Not long after, I saw a couple of trucks idling on the roadside, spaced in a way my brain didn’t label as casual. Growing up on the Navajo Nation, you absorb certain stories without asking for them: relatives run off the road, robbed. My body tightened because I recognized the shape of a setup, even if I didn’t know the language of this specific place. A big van on a remote road, low light, nobody around.

Then the trucks came ripping past later, laughing in the universal language of young men and horsepower, one of them filming vertically out the window like the road itself was content. Nothing happened. But the moment did its job. It reminded me that paying attention is part of the price of being out here—and that “out here” isn’t a backdrop. This peninsula is going through real shit. Cartel logistics, military presence, communities caught between forces they didn’t choose. I wasn’t driving to a museum. I was driving through a place where history is still being written, most of it not for tourists. The cave paintings sit inside that, not outside it. They’re not preserved in some sealed-off past. They’re part of a landscape that’s still contested, still dangerous, still alive.

In the morning, I walked up through granite that looks smooth until you’re close enough to see the stippled grain and seams. The shelters up there aren’t caves in the movie sense. They’re geology deciding to make a roof, a pause in the weather. That pause is everything. It’s why pigment can last.

And then the paintings appear—not as a reveal, but as a correction. You’re looking at stone and shadow and mineral streaks, and you realize some of the lines are not geology. The scale hits first. Some human figures are bigger than a person. Red dominates, but not only red. Blacks, whites, yellows. Pigments that read as mineral and local, like somebody learned the palette from the ground itself.

This tradition is often called the Great Murals, and “mural” is the right word because these aren’t small, private sketches. They’re monumental panels: people, animals, hunting tools, sometimes stacked and superimposed as if the wall is keeping a running ledger. Some human figures repeat in recognizable postures across sites, like a shared grammar. That repetition suggests a practice, not an accident.

Dating rock paintings is hard. Pigment is mostly mineral, and minerals don’t come with a timestamp. What you’re trying to date is the organic material trapped in it. Still, some radiocarbon dates have come back in the neighborhood of nine thousand years before present. Others are much younger. The simplest interpretation is that this wasn’t one “era” of painting. It was a tradition maintained across thousands of years.

At European contact, this central stretch of the peninsula was Cochimí territory—communities adapted to an arid interior and to a life where movement and place-knowledge were inseparable. Whatever else these paintings are, they aren’t random.

The “why” has never been a single clean answer, and I don’t want one. People have argued for hunting magic, territorial signaling, ritual performance, social memory. All of those can be partially true without one of them getting to be the whole story. What feels hard to dismiss is the investment. Preparing pigments, hauling them into canyon country, working at scale on rock that isn’t forgiving, doing it over and over. That’s organized labor. That’s specialists. Whatever the paintings “meant,” they meant enough to keep making.

This is also where the Jesuits arrive and embarrass themselves. Late 1600s, missionary toolkit fully deployed: rename things, categorize people, translate a living world into something that fits a European filing cabinet. They see these paintings, they record them, and then—in their notes—they insist the Cochimí didn’t make them.

Depending on the account, the authorship gets outsourced to giants, or to vanished earlier people conveniently exterminated. It’s a specific kind of logic: yes, the people are right here, and the materials are local, and the paintings sit on their land, but have we considered the possibility that a separate race of eight-foot-tall artists came through, knocked out a few monumental panels, and then disappeared?

These are the same men who wrote calmly about miracles and resurrection. Faced with the idea that Native people could plan, scale, and execute a painting tradition over generations, they suddenly needed a more plausible hypothesis. Giants, apparently, cleared the bar.

Standing in front of the wall, that posture collapses. The paintings don’t feel like an anomaly. They feel like people who knew this place intimately, choosing the right shelter, collaborating with geology, building something meant to persist.

Coda: what counts as a mark

I left because the question started looping in the background like tinnitus. Films published. Money in the bank. Next deliverable. A life that, from the outside, can look like it is adding up. And then: what’s it all for?

I have an answer I use when I’m functional. To be Native, alive, and not trapped in a doom loop of inherited trauma is already an achievement. To keep ourselves from slipping into the abyss people keep marketing as “collapse” is good enough. Most days that answer holds. Some days you need a different scale—something so old and so indifferent to your inbox that the question loses its teeth.

Baja gives you that scale without pretending to be your therapist. It just sets conditions. Long distances. Water as logistics. A string of military checkpoints where men in fatigues ask where you’re coming from and where you’re going. The world is not a feed. It’s a place with consequences and a memory.

Once your nervous system stops flinching at every interruption, you start noticing what people do when they want to be remembered.

Back home, we rename things, announce legacies, sign papers like signatures are geology. Some of it will last, not because it’s meaningful, but because concrete and budgets have their own momentum. The wall is the cleanest example. It’s a scar that will outlive the ego that keeps posing next to it. My hope in the next hundred years is that we remove parts of it—not as symbolism, but as a real decision to stop maintaining something stupid.

The trip kept throwing a quieter question at me: who gets credit for the things that endure?

I kept thinking about the old European trick of encountering something Native and impressive and immediately filing it under *mysterious vanished people*, as if competence requires a costume and a disappearance. We’re forever trying to decide whose hands count as history.

Then there are the paintings, which don’t care what you think about them. Figures bigger than a person. Pigment that still holds its nerve. A practice sustained across thousands of years. That number is so large it stops being “old” and becomes a different category of thinking. It makes most modern legacy talk sound like a man arguing with his own reflection.

On the cobbles outside, I saw coyote tracks stitched across stone like cursive. Clean, narrow, confident. No plaque. No credential. Just evidence of a life moving through a place it belongs to.

Later, on the empty beach, I watched my own footprints appear in damp sand, crisp for a few minutes before wind started softening them. That’s the honest timeline for most of what we do. We make marks. They fade. We pretend otherwise.

The trip didn’t cure the loop. It did something more useful. It re-scaled it.

There are marks you can see, and there are marks that change a system. A president can rename a thousand things and still leave nothing that matters. But decisions about rivers, barriers, extraction, restoration—those are marks that outlast the people who make them, because they rewrite the terms of life.

The Great Murals lasted because someone chose the right shelter, the right pigments, the right scale. They lasted because the environment decided to hold them. Xe Juan Hernández is betting on the same logic, updated for an era when “the sky” includes Google Earth. Whether it works is a question his great-great-grandchildren will answer, not him. That’s the deal you make when you build for deep time. You don’t get to know.

Which is why I keep returning to the two images that bookended the whole drive. The giant bird near Mexicali, designed for eyes in the sky. And the handprints in pigment inside a shelter, designed for a human body standing quietly in the rock. Both are proof that we’re capable of deliberate, lasting change if we choose it. The only real question is whether we spend our time chasing superficial marks, or building the kind that future people can still recognize as intelligence.

The drive back felt faster, the way return trips always do. Our brains are wired to slow down for novelty and speed up for the familiar. The road I’d crawled down cautiously now unspooled like something I’d already solved. Crossing back into the U.S. felt more dramatic than it was—the machinery of inspection, the shift in air, the sudden familiar signage. But I was returning with something. A fresh perspective. Images. And the quiet sense that the loop, when I got back to it, might feel different. Not fixed. Just re-scaled.

So beautiful! I appreciate what you do

This writing resonates so deeply I am, at once, delighted and mystified.

I imagine I will be returning to it again.

Thank you!